Illinois intercity rail transit reshapes funding and service

23.11.2025

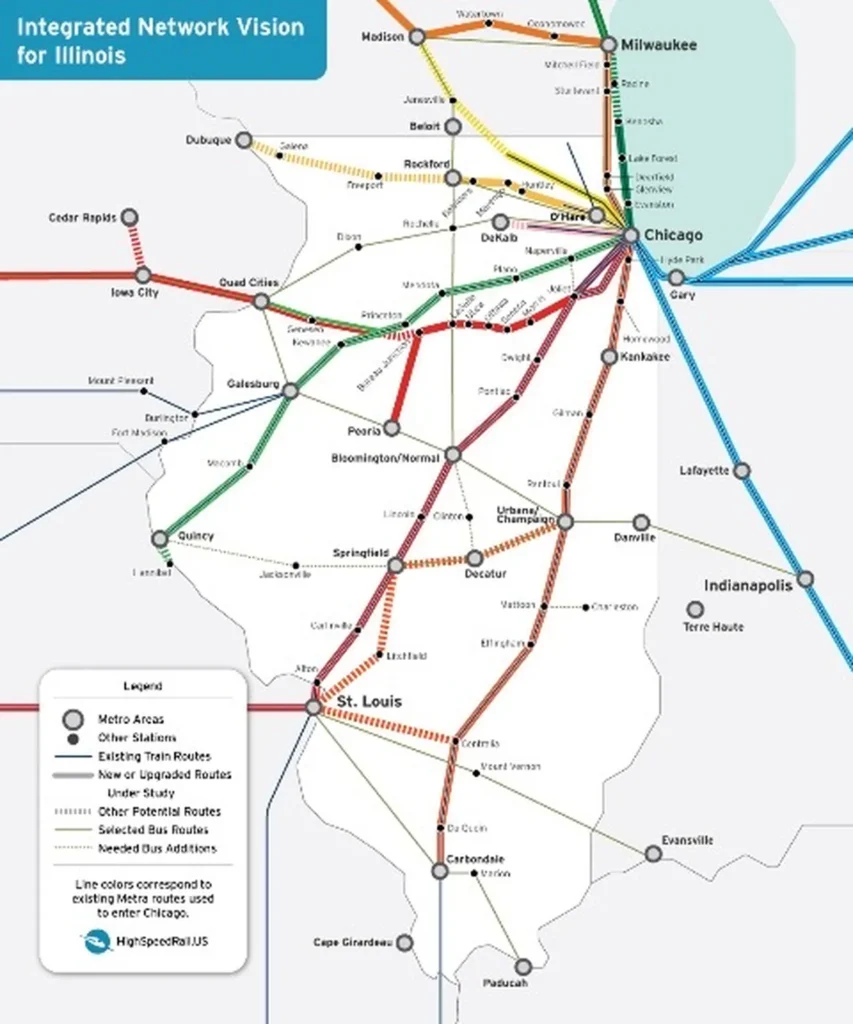

Illinois intercity rail transit is being reshaped by a $1.5 billion package adopted by the General Assembly and detailed by the High Speed Rail Alliance. The measure does more than plug budget gaps: it locks a new vision of passenger rail and public transportation into Illinois’ economic and social model.

This is reported by the railway transport news portal Railway Supply.

This Illinois regional rail legislation doesn’t simply change how trains are discussed; it rewrites the rules that govern them. The term “regional rail” now appears in state law twice, and lawmakers require a working pilot within 14 months. For the first time, intercity passenger trains can draw on hundreds of millions of dollars from state transit capital programs. In parallel, the Act creates a dense set of institutional tools — committees, oversight roles and coordination mandates — intended to pull trains, buses, sidewalks and trails into one integrated mobility system.

So this is not a routine maintenance bill. It functions as a network-building plan. With it, Illinois is trying something that only a handful of U.S. states have even considered: a modern, frequent, interconnected rail system that treats mobility as core infrastructure rather than a social service reserved for those without cars.

How Illinois intercity rail transit enters the capital arena?

For decades, U.S. policy drew a firm line between “transit” and “intercity rail.” Local buses and commuter trains sat in the transit column, with their own agencies, budgets and priorities. Intercity rail largely meant Amtrak, funded through federal appropriations and managed in a separate silo. That divide shaped budgets, governance and planning, and meant that coordination was rare.

Illinois has now deliberately blurred that frontier and folded intercity passenger rail capital funding into its main transit toolkit. Under the new law, intercity trains can access the Downstate Transit Improvement Fund and the Downstate Mass Transportation Capital Improvement Fund. As Capitol News Illinois notes, Senate Bill 2111 steers $1.5 billion into transit across the state while also overhauling governance in the Chicago region. Conceptually, this marks a shift: trains linking Chicago, Quincy and Carbondale are now treated as part of the public transportation system, not as a separate category.

Those capital dollars can finance several types of projects:

- Station projects and upgrades: new or improved platforms, fully accessible facilities and better passenger amenities;

- Grade separations: removal of level crossings that constrain speeds and pose safety risks;

- Track and signal work: improvements that support faster running times, more reliable operations and extra frequencies;

- Planning and engineering studies: technical groundwork for extending routes to new destinations.

The law still sets caps on total intercity rail spending, but the precedent is established. A Chicago–Quincy or Chicago–Carbondale train now sits in the same policy frame as a bus in Peoria or a commuter service to Naperville. All are treated as parts of one network, all respond to mobility needs and all qualify for state investment.

Two planning studies highlighted in the statute show how broad the ambitions are.

Joliet Hub Study. IDOT must carry out a planning study for upgrades at Joliet station to enable potential extensions of passenger rail to Peoria and other destinations beyond the six-county Chicago metro area. In doing so, Joliet is cast as an intermodal hinge — a node where Chicago-area commuter services, downstate intercity trains and future bus links can converge.

Kankakee Extension Study. Metra is required to examine an extension of the Metra Electric Line from University Park south to Kankakee, a city of about 26,000 residents located 56 miles from downtown Chicago. The study is important for Kankakee itself and for what the corridor might become if it continues to Champaign. Adding two tracks and overhead electrification could allow this route to take over the Saluki segment with hourly or better service and trips of under two hours. The idea is technically feasible with the right infrastructure and would expand access to jobs, education and opportunity along the line. How the study defines its scope and assumptions will show whether Illinois aims for incremental improvements or for a full-fledged intercity rail corridor.

From commuter rail to a regional rail network

A central feature of the Act is its explicit embrace of regional rail service in Illinois, breaking with the long-standing commuter rail model.

The traditional commuter pattern is familiar: trains run into downtown in the morning peak and back out in the evening, with limited midday and weekend service. That schedule reflects a classic 9-to-5 office commute and matches a shrinking portion of actual travel behaviour.

Regional rail reverses that logic. Service is frequent in both directions all day, supporting reverse commutes, midday trips, evening outings and weekend travel. In practice, it resembles an urban metro stretched into suburban and exurban territory: passengers should be able to turn up and ride without carefully checking a timetable.

Don’t miss…Brightline West bond exchange plan backs rail funding

Illinois does not leave regional rail as a concept on paper. The law requires concrete steps. By 1 January 2027, Metra must launch a Rock Island Line regional rail pilot — a new scheduling programme aimed at improving transit access for residents of Will County and southern Cook County. The line serves South Side neighbourhoods such as Beverly and Morgan Park, runs through communities including Blue Island and Tinley Park, and ends in Joliet. Earlier in 2025, the Rock Island County Board reaffirmed its backing for the Chicago–Moline passenger rail project, as reported by Railway Supply, underlining how this corridor fits into broader Illinois intercity rail transit plans. This mix of urban and suburban contexts makes the line a natural testbed for all-day, bidirectional, high-frequency operations.

The statute then broadens the lens, reshaping how the regional rail system is overseen. The Northern Illinois Transit Authority (NITA), which replaces the RTA, must adopt service standards by 31 December 2027. Those standards have to address whether commuter rail in the region should shift toward a regional rail pattern, or whether existing commuter service is retained and complemented by regional rail operations.

NITA is tasked with three key steps:

- studying international best practices from metropolitan areas with similar population and economic profiles;

- developing metrics to measure transit propensity;

- creating line-level performance indicators and publishing them each month.

This is not aspirational language. It sets out a detailed directive that effectively legislates a transformation in how suburban rail service is supposed to operate.

Other key priorities in the legislation

Beyond rail operations and funding, the Act moves a set of other priorities that point toward a more integrated, rider-oriented network and tie Illinois intercity rail transit more closely to local services.

South Shore Line access to the Loop and South Side. Riders at Metra Electric stations such as 57th Street or Van Buren have long faced a paradox: South Shore trains stop at their platforms but cannot pick them up for trips into the Loop or toward Indiana. The new law bars Metra from signing agreements that stop the Northern Indiana Commuter Transportation District, which operates the South Shore Line, from boarding passengers at Metra-operated stations. In practice, this unlocks additional options for South Side riders and makes better use of existing rail capacity.

Bus rapid transit and priority treatments. The Act directs IDOT, the Illinois Tollway and local governments to work with NITA and transit operators to support bus rapid transit and bus-priority measures on expressways and major roads. It calls for coordinated assessment of tools such as buses running on shoulders, queue jumps, traffic signal priority and dedicated bus lanes. The logic is straightforward: buses can move far more people per lane than private cars, so the network’s design and operation should reflect that efficiency.

Accessibility and first-/last-mile integration. Access improvements are built into normal practice rather than treated as extras. When roads are rebuilt, features such as sidewalk links to stops, boarding pads and shelters can be included as standard elements, with NITA support. Instead of isolating access as a separate project, the law weaves it into routine street work.

A new Transit to Trails Grant Program aims to connect transit riders to parks and outdoor areas, with a focus on communities that have historically lacked good access to nature. Transit agencies may also partner on residential and commercial development within a quarter-mile of public trails. This encourages walkable neighbourhoods that support transit ridership and capture some of the value created by better access, while leaving land-use decisions under local control.

Institutions, one network and rider voice

Ambitious objectives often fall short when no institution is clearly responsible for implementation. Illinois tries to avoid that by building new structures for NITA transit integration in the Chicago region and beyond.

Transit Integration Policy Development Committee. Located within IDOT, this committee is meant to embed transit considerations at the core of state roadway planning and delivery. It brings together IDOT leadership, modal and highway staff, regional planners and local transportation partners. Its remit is to coordinate early input on projects, identify and strengthen key transit corridors, and develop roadway and design standards that support both buses and intercity rail. In effect, it nudges IDOT away from a strictly highway-oriented role and toward a model where roads and transit are designed as parts of a single network.

“One Network, One Timetable, One Ticket.” The law instructs NITA to run the metropolitan public transportation system so that it functions as a single network from the rider’s point of view. Individual service boards continue to set fares, standards and schedules, but coordination is no longer optional. The target is seamless transfers, aligned timetables and unified fare media — features that are standard in many mature transit systems.

Riders Advisory Council. NITA must set up a Riders Advisory Council with five to fifteen members. This body is charged with advising on policies, service, budgets, fares and service standards. It must receive staff support and sufficient time to review plans before the NITA Board votes, and its membership needs to reflect the demographic and modal diversity of the region’s riders.

Transit as a core climate strategy

The Act also anchors climate policy inside the transit brief. NITA is directed to work with IDOT, the Tollway Authority, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning and other public bodies “to assist them in using investments in public transportation facilities and operations as a tool to help them meet their greenhouse gas emission reduction goals.”

Legislative findings underline that transportation accounts for roughly one-third of Illinois’ greenhouse gas emissions and that public transportation moves people with lower emissions than other motorised modes. On that basis, the law elevates transit expansion to a central climate mitigation tool and positions NITA to access climate-related funding streams that might not otherwise be available to transportation agencies.

Why Illinois now matters nationally?

Taken together, this package does something rare in U.S. transportation politics: it writes a coherent vision into law.

In many states, transit is framed as a fiscal or social burden to be managed — a service for people without cars, a budget item to be trimmed, a system to keep from failing. Illinois, by contrast, places transit, intercity rail and active transportation in the category of strategic assets to be expanded, upgraded and stitched together into one network.

The Rock Island Line regional rail pilot will test whether frequent, all-day service can genuinely shift travel patterns. New capital eligibility for intercity rail will show whether downstate cities can be tied into a coherent network. The Transit Integration Policy Development Committee will test whether a historically highway-centric agency can consistently plan roads and transit side by side. And the one-network mandate will indicate whether multiple operating agencies can deliver a single, understandable experience for riders.

Not every element will work perfectly at launch. Some parts will require adjustments, long-term funding and institutional learning. Yet the direction is clear. Illinois is no longer focused on preserving a mid-20th-century transportation model; it is trying to build a 21st-century mobility system that matches contemporary economic geography, varied work patterns, climate obligations and expectations for real travel choices.

The focus now moves to implementation — and other states have good reason to watch what happens next, as Illinois has quietly become the most important state to follow on transit and rail policy.

News on railway transport, industry, and railway technologies from Railway Supply that you might have missed:

Find the latest news of the railway industry in Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union and the rest of the world on our page on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, read Railway Supply magazine online.Place your ads on webportal and in Railway Supply magazine. Detailed information is in Railway Supply media kit